As the American Thanksgiving holiday approaches, many may experience internal and external conflicts regarding perceptions about gratitude, togetherness, and the history behind the fourth Thursday in November. Do the realities of displacement and damage, discord and strife, render this holiday into a hollow charade, or even a harmful fiction? Is it possible for the complications and complexities of our relationships to food, family, community, and our nation to be received in a manner that will nourish connections?

As in all cultures, among the Anishinaabek (Great Lakes Indigenous) people, ancestral traditions largely revolve around food security and sovereignty. I have learned that there are stories and teachings connected to all foods, whether traditional or contemporary. From the Whitefish clan who sacrificed their own lives in an age-old treaty to ensure the survival of all Anishinaabe just so long as we respect and protect the waters that are their home, to the continued presence of fry bread at celebratory gatherings. Though we know fry bread is the unhealthy by-product of government rations that marked the complete loss of our food sovereignty, it also symbolizes the unquenched determination to give each other the very best we could despite even the most catastrophic circumstances. Alongside struggles that cannot be ignored, there remains the necessity of showing love.

In this sense, the act of eating means we are literally imbibing history, from pre-contact to the present. If the baseline of consciousness and expression rests in experiential, shared reality, what and with whom we eat is indeed a universal variant of life on Earth. Because central to traditional patterns of life and travel, food is ingrained in Anishinaabe stories that guide morality, alongside best practices for planting, hunting, harvesting, and cooking. Parcel to the achievement of Minobimaadziwin (the good life), these guiding stories invariably focus upon the central tension between gratitude and greed. It cannot be overstated how consequential this struggle is to Anishinaabe instructions, as illustrated by the example of the Wiindigo - an insatiable monster of greed that grows ever larger and hungrier in proportion to its excess. This compulsive consumption also causes the Wiindigo to become ever more emaciated in body and in the capacity of the heart, resulting in a tortured state of ceaseless spiritual withering and alienation.

I cannot help but link the cautionary tales of the Windigo to the broken parts of our current food system, as it subsidizes profit at the expense of security, sovereignty, stewardship, and respect. The industrialized, extractive model of Big Agriculture’s industrial monopolies impoverishes small, legacy farmers; poisons water; abuses animals; destroys topsoil; and altogether operates in a manner that is inextricable from alienation. As we observe how this greed-driven alienation from good food intertwines with the removal of Indigenous people from homelands (here and in Africa), in the waves of displaced small farmers, in the loss of fertile soil and drinkable water, what is the proper and necessary response? This is where the immense potential of Thanksgiving resides, should we orient ourselves to embracing the word as a practice and commitment.

We can begin by extracting ourselves from a market-driven, mistaken sense of what is “convenient,” to instead consider what is worthwhile. Smaller scale, localized farming; keeping home and school and community gardens; envisioning our relationship to cooking as a way to show necessary care - none of these come with the seeming ease of mechanization, but all can replenish spirits burdened by alienation. Though currently shackled to an exploitative system, we are the ones whose actions ultimately determine the way our lives are composed. We can claim our ability to take care together, as a priority and a daily given task that begins with gratitude as the antidote to greed.

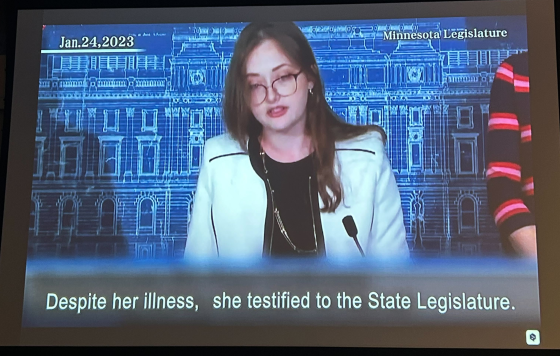

I am grateful for the upcoming Thanksgiving meal marking the bountiful harvests of these lands. I give thanks for the resurgence of Manoomin camps, for seed savers, for gardens, for the animals who gave their lives in the hunt and those whom we must ask for forgiveness and liberation from the cruelties of brutal industry. Much gratitude to all environmental activists and truth tellers who push back against a system that favors the corporate bottom line at the expense of the basics of survival. We need water, we need soil, we need insects, we need diverse seeds, we need to grow and cook and gather together. Let us be gratefully, humbly, lovingly dependent upon this living Earth. The polluters for profit can’t stop all of us at once. Should we choose to heal people, water, plants, and animals in the places we are, food provides the most intimate measure of health. Thanksgiving can be a powerful action, committed to food sovereignty, and nourished by love.